Motobu Choki sensei - 本部流 - Motobu-ryu -

Motobu Choki sensei

Upbringing and training

Motobu Choki sensei was born April 5, 1870, into an aristocratic Ryukyuan family. The third son of Motobu Aji Choshin and his wife Maushi, Choki sensei was called Masanraa as a child: "ma" being a polite prefix and "sanraa" meaning "third son." This is one theory for the source of his later nickname "saarū," or "monkey," which can also be pronounced "saaraa." From a young age, he had an interest in the martial arts, and his formal training began at the age of 121 along with his eldest brother Choyu sensei under the Shuri-te master Itosu Anko, who was invited to their family home to instruct them.

Being 13 years younger than Choyu sensei, Choki sensei always lost to him in kumite. Because of this, he secretly sought instruction from other legendary masters such as Matsumura Sokon sensei of Shuri and Sakuma sensei while still training under Itosu sensei. Matsumura sensei was such a great martial artist that Choki sensei said of him, "among recent karate masters, there was no one as exquisite or strong." A direct student of Choki sensei at the Daidokan dōjō, Matsumori Masami, has also said "Motobu and Yabu were Matsumura sensei's prize students," so it seems that Choki sensei and his good friend Yabu Kentsu were favorites of Matsumura sensei.

Sakuma Pēchin was a contemporary of Matsumura sensei, and they were both regarded as the pre-eminent Shuri-te masters of their time. In his Watashi no karate-jutsu, Choki sensei praises Sakuma Pēchin as "Sakuma the Wise." It may have been because of Sakuma sensei's sophisticated understanding of karate and logical teaching methods that Choki sensei's kumite abilities developed so quickly.

From the age of 19, Choki sensei also studied under the Tomari-te master Matsumora Kosaku sensei. Choki sensei's abilities in kumite training seem to have made an impression on Matsumora sensei, who is said to have remarked, "for a young man, he is extremely talented in the martial arts" (reported in the Ryukyu Shimpo, 1936).

Choki sensei sought instruction from all the great martial artists of his time and immersed himself in first-hand research into karate. At a time when it was difficult to receive training from even one master, it was Choki sensei's origins as a son of a family of the udun rank that enabled him to do this.

Choki sensei also did something unprecedented for a person of noble birth at the time by venturing into Naha's red-light district of Tsuji-machi to take part in street fights known as kakedameshi. At a time when karate was still a martial art studied only among the military class, it was inconceivable for anyone of that class to flout propriety by fighting in such a dangerous place. A loss in such a situation would not only be physically dangerous, but would also bring shame upon one's family. Thus, a person of noble birth such as Choki sensei taking part in such fights was unheard of.

However, Choki sensei was rational by nature and believed in the authenticity of experience. He sought to verify the usefulness of the techniques he had learned from his teachers in actual confrontations. In hundreds of kakedameshi encounters, he did not lose even once. As a result, by the time he reached his mid-twenties, his nicknames of Motobu Udun no Saaraa-umē (Lord Monkey of the Motobu Udun) and Motobu no Saarū (Motobu the Monkey) were known throughout Okinawa.

Choki sensei had become a living legend while still only in his twenties, but because his desire to improve his bu was stronger than others', he subsequently immersed himself in research into kumite with his fellow student Yabu sensei. Whenever they encountered a problem or question, Choki sensei would seek guidance from his teachers. Determined not to let his abilities go to his head, Choki sensei began an earnest and humble investigation into the heart of karate that continued into his old age.

1. According to the old style of reckoning age, by which a year would be added at the start of a new calendar year. By Western reckoning, he was still only 11.

Life on the Japanese Mainland

In 1921, Choki sensei moved to Osaka. In November of 1922, while visiting Kyoto, he saw a sign advertising matches of judo vs. boxing. Impulsively jumping into a match himself, Choki sensei downed his European boxer opponent in one blow. At that time, Choki sensei was 52.

In those days, it was still said that "life is 50 years." Therefore, the spectators were astonished to see a man considered elderly take down such a huge boxer using an unknown martial art, and after the match they were caught up in wild enthusiasm.

Choki sensei was already a legendary karate-ka in Okinawa, but after the match his reputation as a martial artist began to spread on mainland Japan, and he was besieged with inquiries about karate and requests for instruction. In 1922, he established a dōjō in what is now Osaka's Konohana Ward, and also instructed at the Mikage Police Department and Mikage Normal School in neighboring Hyogo Prefecture.

In 1925, the magazine Kingu, which had the largest circulation at the time, gave the story of Choki sensei's victory in Kyoto extensive coverage. It is from this article that many people in Japan first heard of the Okinawan martial art of "karate." The people of Okinawa, who were suffering under harsh economic conditions at the time, were glad to hear news of the success of one of their own on the Japanese mainland.

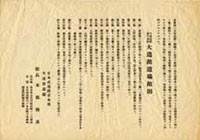

In May of the following year, Choki sensei published his Compilation of Okinawan Kenpo Karate-jutsu Kumite. This volume is the oldest record of kumite, and the classical

Okinawan kumite techniques introduced in it are today preserved only in Motobu kenpo. As such, it is not simply the kumite manual of one ryūha, but a priceless document

of Okinawan culture and history which is held in high regard both in Japan and around the world.

Tokyo and the Daidokan

In the late 1920s, Choki sensei moved his base of operations to Tokyo while his family remained in Osaka. In 1929, he became shihan of the Toyo University karate club. Around the same time, he established the Daidokan dōjō in what is now Tokyo's Bunkyo Ward.

The exact date of the Daidokan's establishment is unknown, but the few existing records seem to indicate it was functioning by 1930. The dōjō was located on the first floor of a rented house and was extremely modest. However, its historical importance comes from it having been the oldest formally named dōjō dedicated exclusively to karate in Japan. In naming it, Choki sensei was inspired by the Zen verse "daidō mumon," intending to express that the path to becoming a great martial artist can be found by seeking understanding of karate by one's own initiative, as he himself had done.

In 1932, Choki sensei published his second book, Watashi no karate-jutsu. In this volume, he appeared in photographs of the entire sequence of naihanchi. Moreover, he strongly warned against misinterpretations of naihanchi and expressed concern about what he saw as the distorted state of karate on mainland Japan. In particular, his conservative postion regarding alteration of kata came from his opposition to other karate-ka doing so solely to expedite the promotion of karate on the Japanese mainland.

Choki sensei also strove to record the names and specialties of the martial artists of the Ryukyu Kingdom and preserve the oral traditions of karate history that he had heard from his teachers. Today, Watashi no karate-jutsu is considered the primary document regarding the history of karate.

In 1936, Choki sensei briefly returned to Okinawa for karate research, and on October 25 took part in the Ryukyu Shimpō-sponsored "Karate Master Symposium." The historical significance of this symposium was so great that October 25 was officially declared "Karate Day" by the Okinawan legislature in 2005.

In addition, a one-man symposium with just Choki sensei was held on November 7. The contents of this symposium were covered in a series of three newspaper articles titled Listen to the "Real Fighting Stories" of the Venerable Martial Artist Motobu Choki. The respect accorded Choki sensei in this way illustrates his position as the foremost practitioner of Okinawan karate at the time.

In this later symposium, Choki sensei reiterated his dissatisfaction with the state and direction of contemporary karate. He criticized the alteration of kata from their characteristics during the time of Matsumura sensei and Sakuma sensei, as well as the presumptuous creation of kumite with no connection to tradition by a generation with no knowledge of the classical kumite of the Ryukyu Kingdom. However, the subsequent history of karate indeed went down the path Choki sensei feared it would.

Latter Years

In 1937, Choki sensei returned to the mainland and resumed instruction at the Daidokan a short time later. At that time, the boxer known as "Piston" Horiguchi sensei (1914-1950) received training from Choki sensei there. In addition, as the Daidokan was close to the Kodokan dōjō, the jūdō master Toku Sanpo sensei (1887-1945) and others would often come by. When Choki sensei would return to Osaka, he would also give instruction to his son Chosei sensei.

Unlike his elder brother Choyu sensei, Choki sensei had given up weapons training while still in his youth. However, in his latter years he began practicing ken-jutsu and bō-jutsu once again. His students Nakata sensei and Maruyama sensei later said that Choki sensei's use of weapons was impressive and that his knowledge of weapons seemed to be reflected in the principles of Motobu kenpo.

Then in 1941, Choki sensei closed the Daidokan in Tokyo and briefly returned to Osaka. He remained there until the middle of 1942, when he left for Okinawa. At first, he had planned only a short homecoming, but as the war intensified and returning to Osaka became difficult, he decided to see out his last days in the place of his birth.

During the war, as blackouts started against air-raids, Choki sensei is reported to have said "The war is lost. A defensive battle is almost impossible to win." Choki sensei passed away on April 15, 1944 at the age of 74. His grave is today in Kaizuka city in Osaka.